“It will be weightless underwater,” I am told as I stare at the eighty-pound helmet that will encapsulate my head. On my mind is that a stingray accidentally killed the Australian diver and conservationist Steve Irwin, not that long ago. Our guide tries to reassure us about this shark-related fish, “If a stingray comes near you, it’s because it wants to, don’t scare it!” There is no time to mull over this, I am first in line for my maiden helmet dive.

Our Regent’s Seven Seas “Tahiti cruise” had begun, and would end, in Papeete, the capital of French Polynesia. Today, we experience Moorea, one of the Society Islands—further divided between the Windward and Leeward Islands based on their position within the trade winds—and one of the five archipelagos that make up French Polynesia.

The m/s Paul Gauguin anchored early that morning under the watchful peak of Mount Tohivea, its mountains akin to the jagged teeth of a shark. At its feet, a lagoon of green and blue waters teem with the most diverse collection of plants and animals; it is protected by a barrier reef—consisting of motus (atolls) created by the accumulation of coral skeletons.

Six of us transfer by van to the Intercontinental Moorea Resort & Spa where we meet the Aquablue Helmet Dive crew. During the ten-minute boat ride to the diving spot on the lagoon, owner-guide Vincent briefs us on safety, assisted by Jeff, a professional cameraman-diver.

During a Q&A session, two participants discover that the helmet dive is not a walk in an underwater viewing glass tunnel. They relax at the thought that the activity doesn’t require swimming and is safe for children six years old and anyone without health issues. The couple will do the helmet dive, albeit in their touring clothes. Meanwhile, my neoprene booties boost my sense of security, as do my training shorts and long-sleeved sun-protective top. I know that a coral scratch can ruin a vacation.

Descending the Shallow Depth

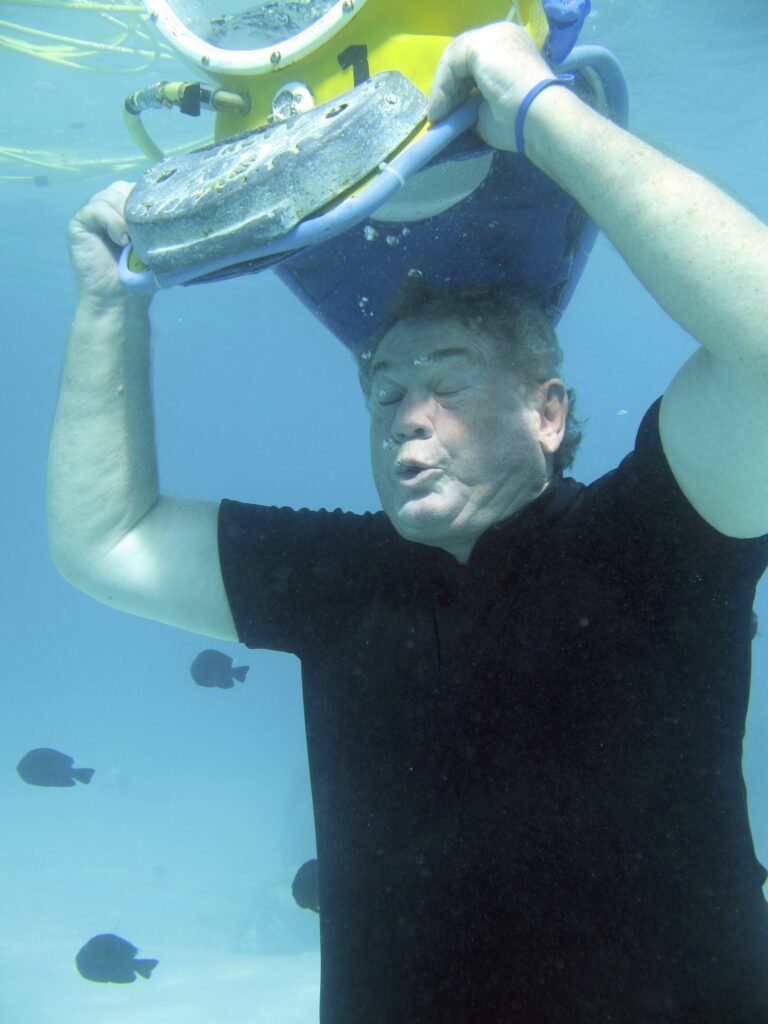

I step down the ladder affixed to the side of the pontoon until I am chest-deep in the water, then Vincent gently places the helmet onto my shoulders. He assists my 16-foot descent, while I cringe at the thought that water might somehow seep under the helmet. I remember my attempt at clearing my mask during my one-and-only scuba diving initiation. I tend to be claustrophobic in some situations.

It helps that I am not strapped to a bunch of equipment, not even a respirator or an oxygen tank. Instead, a flexible tube—connected to the tank on the boat—feeds compressed air inside my ‘breathing bubble’ (to replenish my oxygen supply and purge CO2 buildup).

As soon as I immerse, other than a bit of pressure on my shoulders, the helmet is no longer worth its real weight. And my face is dry (the pressure of the water trapped air inside the helmet). Vincent—in scuba gear—secures my footing onto the sandy lagoon floor, and then I follow his instructions: Go to the side, kneel, and wait for the group.

Underwater Walking

When Vincent signals that we all move forward, it’s easier said than done. The ‘weightless’ helmet keeps me grounded, but water pressure encumbers the walking, my foot slowly rising, and my arms barely propelling me.

I look at my diving companions in a whimsical scene of ambling creatures reminiscent of Tintin in Hergé’s book Explorers on the Moon. When Vincent started Aquablue, in 1998, he wanted to take only certified divers back to history with authentic Russian helmets—the brass and copper kind. But when non-initiated divers kept asking about ‘the underwater walk’ he got the modern yellow helmets we are wearing. Still, they work like the diving bells of the past.

It becomes evident that the only choice is to surrender to slow motion. I feel like I am inside the tropical fish tank at an aquarium. Various shapes with perfect markings in vibrant colors glide by me, some checking out my faceplate. Then a colorful flurry takes me by surprise, the feeding tube held by Vincent spawning the frenzy. When it’s my turn to hold the tube, the fish knows where to go.

Sizing Up Stingrays

My hand on the tube disappears under the fish as if I am holding a big bunch of flowers. Then some gray ‘flying saucer’ makes its way through the fishy crowd: a stingray. I can’t check my husband’s reaction, the helmet only allows frontal vision, so I turn my whole body around and come face to face with two more rays. I am captivated when their undulating and baby-soft pectoral fins gently brush my arm. But when the ray begins to meander around my legs in a cat-style way, I freeze at the thought of the long tail with the serrated—and poisonous—barb (unlike manta rays that don’t have any). And I don’t dare move when one ray takes a liking for my neoprene bootie. Vincent signals that it’s okay, and eventually engages in a playful choreography with the animal. Rewarding it with a treat allows us to see its mouth under its white belly.

Precious Polynesia

Standing on the ocean floor is relaxing compared to treading to stay afloat. I even get close to the mounds of coral heads, scaring a moray eel back into its rocky home. A spotted boxfish speckled like dice, a cubical-colored Picasso fish, a camouflaged rockfish, and fluttering anemones make me ponder the future of this pristine underwater ecosystem. It’s the natural asset, not only of the Society Islands but of all Polynesian waters. I ponder the future of this aquatic web. From phytoplankton to large predators such as whales, all depend on one another for food in a fragile ecosystem, its balance now threatened by human activity and climate change.

After 30 minutes underwater, it’s time to regroup for a photo souvenir. Is the same stingray lounging on my foot again? I can’t tell but, thanks to the feeding tube, the animal lifts off. I was first getting underwater and last coming out of it.

Original article published 2012 Buckettriper.com