We leave the grayness of Tangier’s bustling medina at 66, rue Les Almouhads. Here, the open, massive front door no longer repels assailants. It invites antique ware hunters instead. Boutique Majid owner welcomes us by a trickling fountain. We immediately fall under the charm of a vivid ensemble of colors, textures, and shapes, all from generations past. Textiles, wood trunks, clothing, ceramics, glass lanterns, and carpets compete for our attention. My friend is on a mission to buy fabric, and I have fallen under the spell of the jewelry.

Tribal Jewelry

I see necklaces so voluminous, that I wonder whether that’s what they truly are. ‘Berber heirlooms,’ Majid says. They are strung with uneven, round chunks of pink coral, red carnelian, green amazonite, buttery amber, ebony beads, and silver talismans. I see earrings so large that they are fitted with chains going over the head to lessen the weight on the ear lobe. No wonder these jewels were reserved for ceremonies. I point to intriguing pieces in a repetitive triangular shape. They are fibulas—joining the two sides of an overcoat—and converted into pendants unless designers turn them into wall art, in a box frame.

When I ask about the prices of such treasures, I also point to a comparatively modest necklace. It’s sold by weight, which makes sense. Silver amulets, pink coral, and amazonite beads tip the scale at $700. I learn that bluish-green amazonite is a feldspar thought to be named after a similar green stone found in the Amazon. Only a few gold pieces are sold here—they are deemed evil by Berbers, although not by Arabs.

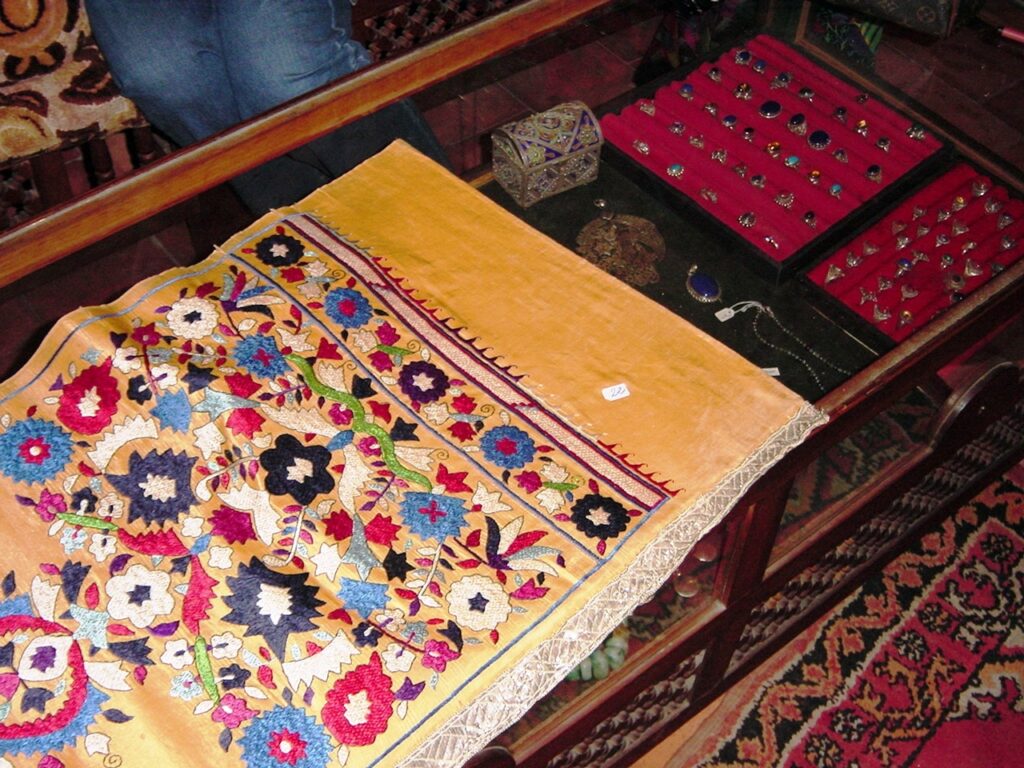

I then sit at a low table that doubles as a display case for silver. Talismans and amulets are engraved, or embossed from medals, coins, and the iconic protective hand of Fatima—Mohammad’s daughter. Another popular amulet is the Southern Cross—guiding caravans, at night, to avoid the intense sun.

Majid brings some of the less extravagant, but still stunning necklaces to the table. His eyes twinkle when I ask who buys these pieces. They are not for sale, and his private collection is meant to save them from being sold as separate pieces.

Jewelry was an integral part of tribal life and believed to heal and protect. They also indicated kinship and wealth—hence the weight. The Berber women of the Rif Mountains—nomads and oasis dwellers—could trade or sell their jewelry to meet the needs of their families. It was therefore a significant part of a dowry and a meaningful gift throughout life. But as tradition faded, so did their authenticity and value. Today, copal resin, and even plastic replace amber for what we call costume jewelry.

With the necklace still on my mind, I join my friend in an alcove akin to a shrine to traditional textiles: heavy wool jackets and vests, colorful cotton dresses, ceremonial outfits, shimmering caftans, and decorated belts. My friend is magnetized by the “energy” left in these old clothes. She falls for a long-sleeved jacket with a worn texture resembling boiled wool. Then she remembers that she is here to buy fabric.

Ethnic Textiles

As an antique dealer, Majid travels throughout Morocco to find the precious fabrics and other items he sells. He restores value to small remnants of cloth abandoned in old family trunks, assembling them patchwork-style into tabletops, throws, or unique purses. All incoming pieces are cleaned and classified according to size, condition, origin, color, and value.

Sewing or weaving was an essential skill for women. Urban little girls received needles, thimbles, and silk threads as gifts, and enjoyed fine embroidering. Instead, nomads and oasis dwellers received spindles, cards, beating combs, and learned weaving out of necessity.

We follow Majid upstairs for another trip into the past. Textiles show divergent styles—geometrical and floral. They are the result of cultural influences. First, from the Arab invasion of what was once only Berber land. Add to this eight centuries of Moors’ dominance in Spain, which ended with the Inquisition. As a result, Al-Andaluz people retreated to Morocco, and with them the Jewish community that brought its traditional skills, too. The French then introduced the Jacquard looms, for pompons, for example.

Majid explains that the floral embroideries on pillowcases and bedspreads are from the Tetouan province—a former Protectorate of Spain. I don’t quite get the difference between the Chefchaouen style and the Rabat style. They use the same technique, sewing a floral motif freehand onto the fabric and then embroidering with thick silk threads to create relief. The difference is perhaps that Chefchaouen specializes in drapes and wall hangings and Rabat in indoor curtains with larger and heavier embroideries, giving them adequate ballast.

Carpets with or without piling indicate a mountain or desert tribe origin. As for the intricate, belted, festive caftans, their use is similar to that of kimonos. We touch brocade, velvet, wool, silk, and cotton fabrics, magnetized by the history infused in these textiles. And then my friend zooms on a fabric.

Tea with The Fez Double Running Stitch

Majid gets animated as he holds the piece. “This Fez fabric must be treasured because it was hand-embroidered,” he insists. “Cutting it would show total ignorance.” Since my friend planned to upholster an antique chair, our eyes meet at the self-explanatory thought of the offense.

Muslim and Jewish refugees brought their weaving and dyeing skills to Fez, in particular. Today, Western designers praise the stately frieze patterns and their monochromatic colors that complement contemporary decors. The double running stitch is so tight that I can’t tell which side is up, a good thing since it’s reversible. And the colors have faded into marvelous shades of foggy blues, ashy blacks, and rosy reds.

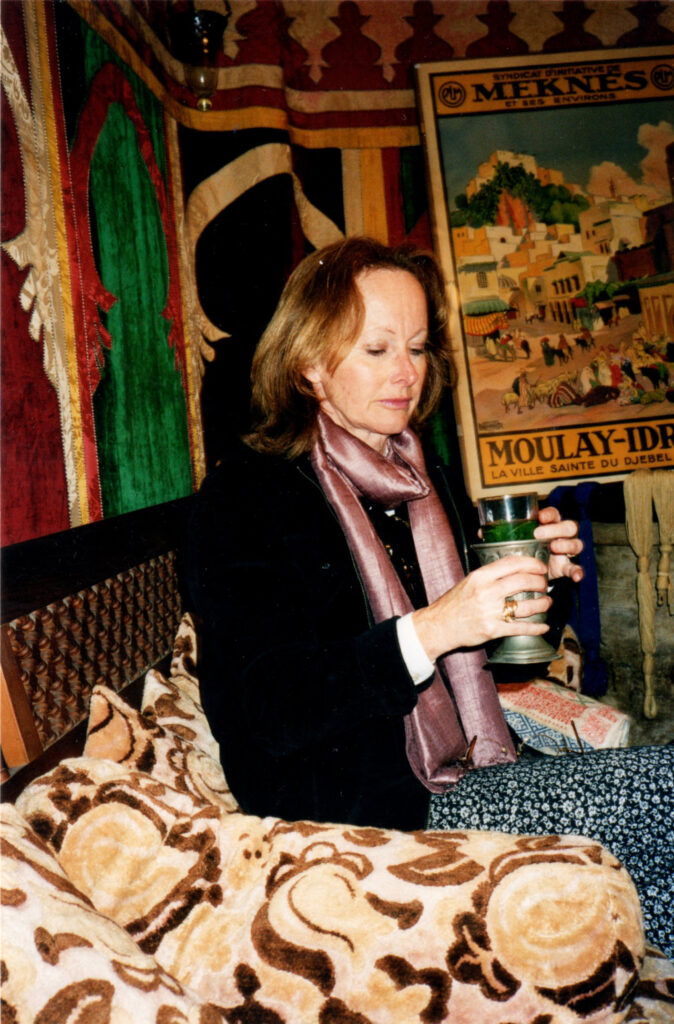

“How much?” my friend asks. Majid leads us back downstairs as he holds the precious one-by-three-quarter yard piece. A teapot of fragrant mint tea and colorful glasses await to soothe the price tag: $800. I sip the sweet potion while gazing at the necklace that caught my fancy. There is no negotiating; the past has a fixed price.

More articles about Morocco:

First published 2012 Buckettripper.com – edited 2024