Dots are everywhere in Sydney and seem to follow me like curious eyeballs. They peek from every shop through vibrant boomerangs, didgeridoos, and other crafts and souvenirs. Surely, there must be more to them than polka dots.

Back to School in an Art Gallery

The first thing I learned from the art gallery curator is that the paintings are concealed messages about the creation of the world according to Aboriginal beliefs, and their knowledge of the land. Trying to understand what I see is like learning to read again. I squint at the seemingly unruly dots that freckle the canvases until I finally discern rows and columns of squares and circles. At times, they form symbols, sometimes grouped into patterns.

Now that I know the concept, the pictorial language becomes logical. A vertical half-oval with two vertical lines represents a man, with one it’s a woman—with none it’s a person—and a small one represents a child. The trilogy symbolizes a family, and several families become a community. I am getting the hang of it. Concentric circles are campsites. Two parallel dark lines represent a river connecting camps. I move on to mountains, waterholes, and ants.

But don’t take my word for it, it’s complicated. Not only do symbols vary with the painter/storyteller, but dots symbolize a learning process, and each dot is a spirit. And it gets more complex with symbols that have multiple meanings and associations that lead to multi-layered interpretations. Aboriginal people learn the sacred messages during their entire lives. With no written language, this is how elders passed on practical and spiritual messages, deciding when and to whom.

At the end of this informal initiation, I step back for an overview of the art, and the paintings suddenly come alive. I know part of an alphabet of sorts, but I still can’t read.

From Land to Canvas

The next day, I am on the three-hour flight from Sydney to Yulara—in the Red Center. I am gazing some 30,000 feet below when a vibrant mosaic catches my attention and magic happens through the lens of my camera. It frames the same intense earthy colors and sometimes shapes I saw on some canvases. I easily identify the black lines of rivers crisscrossing the land in a giant puzzle. It strikes me that the dot paintings I saw are like the sketches of what I see below.

How did Aborigines know what the land looked like from the air? The question hangs as we descend towards the monolith formerly known as Ayers Rock, and as Uluru since the Aborigines got it back in 1993.

The next day, at the Aborigine-run Cultural Centre, I am once again drawn to the dots and more lessons.

Each painting is a story called Tjukurpa, a combination of two mythical concepts. One is the creation of the world, and the other is life guidance passed on by ancestors. The concepts are not translatable but interpreted by non-indigenous people as the Dreamtime and the Dreaming—for a lack of better words.

One example is the Tjukurpa of the Seven Sisters. The women run away from a man, Nyriu, who wants to marry them. They sit at a campsite with their food supplies. A bowl and a stick lay next to one of them. To lure them, he places another bowl and a stick nearby. At each campsite, they leave markings on the land as survival hints. They finally escaped to the sky and became the constellation of the Seven Sisters, still pursued by Nyriu, the brightest star. We know them as the Pleiades and the brightest star as Orion.

Aboriginal Art Forms

Aborigines have always expressed their culture—archeologists found paintings on rock walls dating back 20,000 years. The teller-painters also depicted stories in the sand using natural pigments, charcoal, flowers, or feathers, and as ceremonial body adornments. The stories were about survival—hunting, food gathering, secret water holes—and sacred elements. Since they were nomads, they muddled up their sand pictures before leaving and created new ones at the next campsite. Today, painters roll their Belgian linen canvases and store them away.

Art by Aborigines goes back to the early 1900s. Children sent to missions for assimilation were exposed to visiting artists who introduced them to Western techniques. Then, in the sixties, Aborigines were forced to adopt a lifestyle alien to them until 1971 when a non-Aboriginal art teacher—at the Papunya settlement in the Western Desert—encouraged them to paint traditional motifs on the walls of the school. Women began storytelling too. The elders had found an inspiring way to transmit their culture to future generations. Although not all are dotted paintings they are also referred to as Western desert painting and Papunya art. The genre evolved to include icons of animals and plants.

The Validation of Aboriginal Art

The elders were outraged in the early 50s when paintings began to leave the community. Some still want to protect their heritage by retiring those early paintings from museums. With the resurgence of the art form in the 1970s—plus the prospect of a source of income for their impoverished communities—one elder came up with the dot technique, an abstract way that conceals sacred information from the non-initiated.

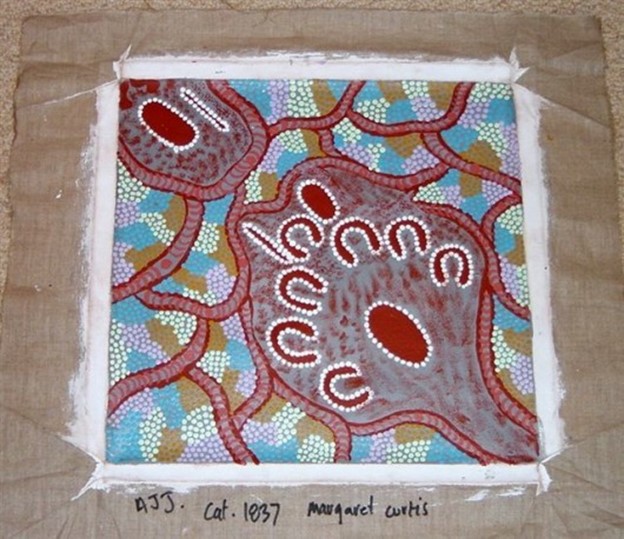

Controversy also happened among foreign gallery curators. First, regardless of talent, they shun Western-influenced, early aboriginal work. Then, they judged early adaptations of sand painting into dot painting—on canvas, with acrylic paint—too simplistic and commercial, and devoid of authenticity. Aboriginal art is now exhibited worldwide, with many artists commanding high prices. One sold for one million dollars in 1986. At a sentimental value of $250, I bought the unframed painting heading this article at the Uluru Cultural Centre, benefitting one of the two aborigines-owned galleries.

As for the aerial view of the landscapes, there is an explanation. Artists sit on the ground, overlooking their work as they traditionally did to create a ‘map’ of the land—with no horizon line. What’s more, there is also no right way to look at the art—horizontally or vertically—or to hang it on a wall. Either way, the story can still be told.

Comments

- Jill Browne says: Thank you for this guide to a fascinating art form. I wonder if it’s one of the oldest in the world. Perhaps it is the oldest surviving, continually practiced form? At any rate, I enjoyed your explanation. April 26, 2012.

- Jo Robinson says: Very informative and well written. Learned more here about the reasons behind the symbology of Aboriginal dot art than from many other sites I have visited, thank you. October 31, 2012.

More about Australia: Sunrise at Uluru

First published April 2012 Buckettriper.com – reviewed 2024