I feel as if I am part of an entourage waiting for the awakening of the Sun King. Except that here at Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park—aka Ayers Rock, in the Australia Red Center—cameras, tripods, binoculars, and phones are contemporary evidence that the real sun is rising and the event not limited to a royal entourage.

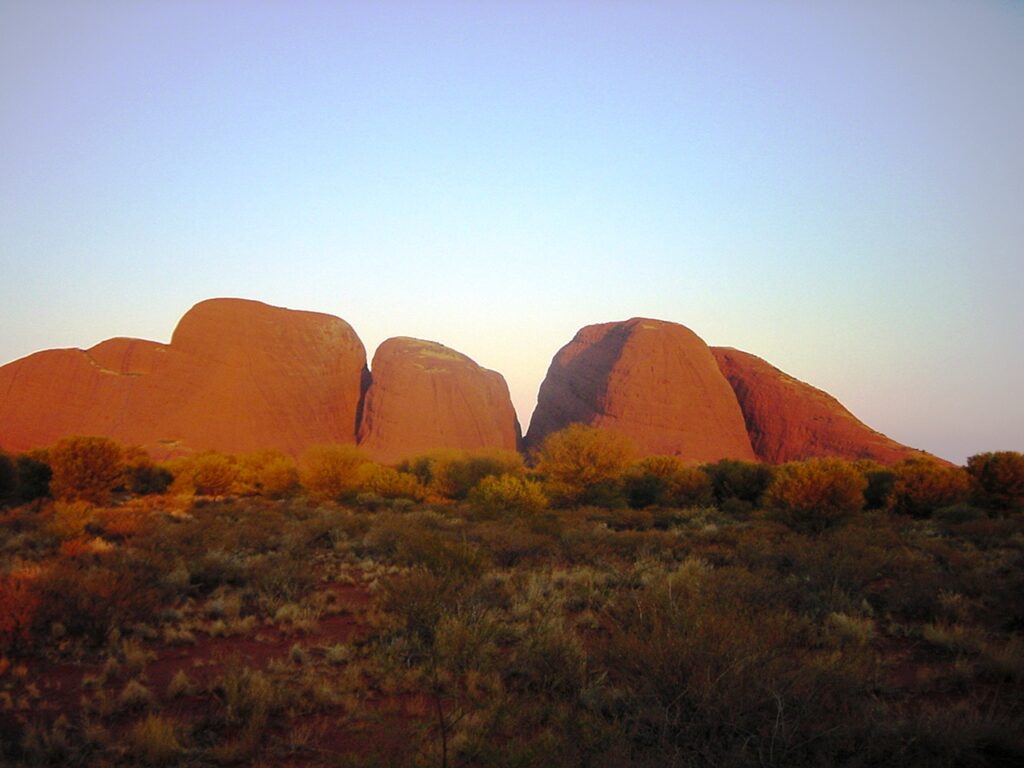

When the aircraft begins its descent toward Ayers’s Rock Airport, I am impatient to see the famous rock. I scrutinize the barren and indeed red land below so I won’t miss it. And there it is. The monolith emerges from the sand akin to an enormous submarine from the ground. As we circle before landing, Uluru then seems to point to Kata Tjuta, a group of boulders referred to as The Olgas.

A Geological Wonder and Sacred Site

Uluru dominates the surrounding desert from its 348-meter-height and three-kilometer-long base, plus some five kilometers underground, according to geologists’ estimation. Less precise is the monolith’s age. The numbers are blurred along the transitions: from the mountain range that it once was to the flat-topped rock that it is now. During that 550-million-year span, sediments, erosion, immersion, wind, and rain left their marks on the land for them to interpret. One irrefutable evidence is the oxidation of the minerals that turned Uluru terra-cotta red.

The sunrise over the giant rock is said to be an unforgettable memory. Climbing it is a bone of contention. On the one hand, the Anangu Aboriginals want the climb to be forbidden for cultural and safety reasons. On the other hand, Australia’s Federal Environment Minister and the Northern Territory’s Tourism Minister disagree. I am going to find out how I feel about it.

Ayer’s Rock Vs. Uluru

Australia’s Red Centre is the driest inhabited desert on earth, yet Aborigines have survived here for 10,000 years. However, things began to change when Australian William Goose discovered the monolith in 1872 and renamed it after Sir Henry Ayers, Chief Secretary of South Australia. A year later, British Ernest Giles claimed the discovery of the 36 boulders and renamed the highest one Mount Olga. Later, self-determination gave back to the Anangu people what first belonged to them: their ancestral sacred site and name.

Uluru and Kata Tjuta are not the only inspiring landmarks in the area, but their geophysical particularities and spiritual ties to the Aborigines earned them designation as World Heritage sites. And heritage it is to the Anangu people who compare it to what a church is to Christians.

The Sun Always Rises on Uluru

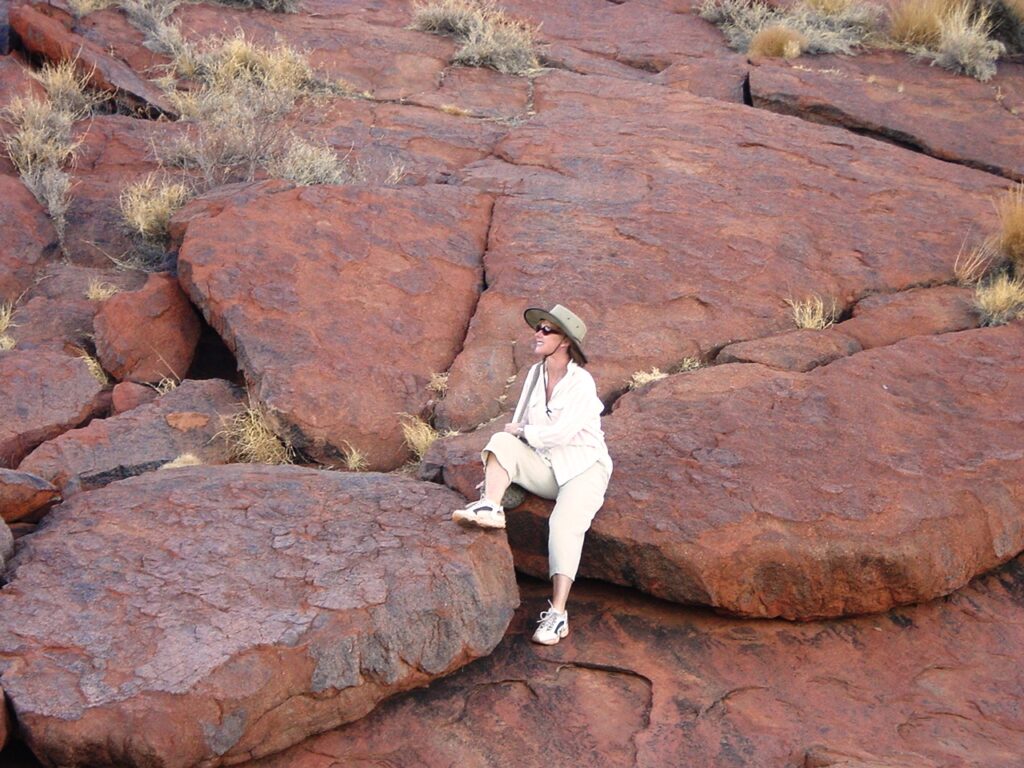

The next morning before the crack of dawn, our group waits for the famous sunrise on to Uluru. We came by van, others by bicycles, Harley Davidson motorbikes, 4W-vehicle, and even by camel. My silhouette mingles with those of other early risers. Perhaps it’s the darkness or the chilling air, but we all whisper as if we are afraid to wake the giant before it is ready. Then it begins to happen. A faint sun ray appears and a harmonious oh-ah escapes from our open mouths.

Total silence follows. As the sun rises, wrapping the dark purple sandstone into glowing hues of ocher, Uluru lightens up inch by inch. In a fleeting moment, the base ignites, and the surrounding desert bursts into life. It’s officially daytime, and the spiritual ancestor of the Anangu people stands gloriously. The experience resonates with the awareness that Nature is the universal place of worship.

To Climb or Not to Climb

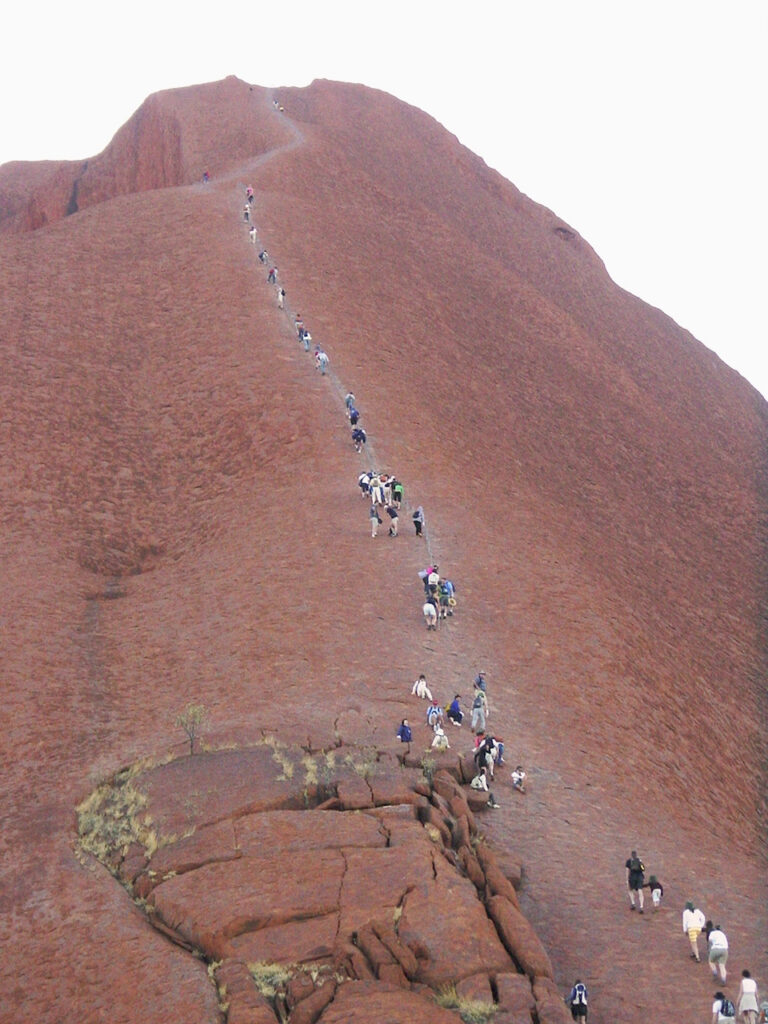

the giant rock appeared smooth from afar, but not so as we get closer on our return trip from the sunrise site. It is poked with large holes, parted with crevasses, and much of its surface erosion is ribbed. And then I see them. Like a colony of giant ants, climbers ascend and descend the 1600 meters—1700 yards—trail in a steady flow along a rope stretched on the incline.

Some of us considered climbing Ayers Rock until our guide shares a message from the Anangu Aborigines. “The real thing is listening to everything and understanding everything.” I get it. It’s one thing to climb Ayers Rock, it’s another to think of it as Uluru.

It’s Aboriginal Law not to climb sacred sites, and sacrilegious to do it. Whatever the Aborigines think of our callousness, it’s also Anangu hospitality to keep visitors safe. People have died here, from heart failure, exhaustion, heat, or falls during their unrealistic attempts to reach the summit.

By the cordoned entrance, some climbers wear hiking shoes, and hats, and carry backpacks. Others are outfitted for a walk on the beach. Returning climbers admit it: the path is unpredictably steeper and the top farther than it seems. The heat is a factor and the arkose—coarse sandstone grains and small rocks—causes back-sliding.

Nearby, I discover plaques screwed on boulders. They are memorials, showing that tragedy struck a 63-year-old climber and a young boy on a school trip, plus a dozen others. In the end, none of us makes the climb.

Some argue that Uluru is a natural site that cannot be compared to a church, a mosque, or a temple. I tend to think that Anangu people were never builders. And I am only a guest in their native land.

Update: Based on the spiritual significance of the site, and for safety and environmental reasons, the climb has been forbidden after a unanimous vote of the board of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, in 2019.

More stories about Australia: Interpreting the Dot Paintings

First published May 2012 Buckettripper – revised 2022