The grand finale of my trip to India is not a massive fort or a sumptuous palace, it’s a mausoleum: the legendary Taj Mahal.

In interviews published in the Indian English newspaper Asian Age, about the Taj’s 350th anniversary (in 2004), Indian celebrities revealed a fascination either with the love story or the harmonious Indo-Islamic architecture. Others pointed to the 20,000 laborers who built it and the extravagant cost that had bankrupted the State of Uttar Pradesh.

Much has been said about the Taj, yet it continues to move everyone differently. I am about to have my own experience as a foreign visitor.

BACK TO HISTORY

The Mughal emperor Shah Jahan and his favorite wife—Mumtaz Mahal–were inseparable, she was even his closest adviser, following him on military campaigns until she died while giving birth to their 14th child, in 1631. Grief-stricken, his last gift would be a monument as magnificent as the love, to which he devoted his life.

However, the emperor’s endless and costly obsession with magnificence led their son Aurangzeb to depose him for abuse of power. Shah Jahan died as a prisoner in the Red Fort, 30 years after his wife. Myth or reality? He intended to build a black Taj Mahal as his own mausoleum.

Today, the Taj Mahal it’s a UNESCO Heritage Site and is unofficially deemed one of the New Seven Wonders of the World.

MEETING THE TAJ

Some visitors arrived in Agra by the Shatabdi Express train from New Delhi. We arrived by coach then transferred to an electric shuttle, one kilometer or so from the Taj, to limit gas pollution.

Anticipation is palpable as we silently walk toward the ramparted compound, then come to a standstill in the funnel of the roofed main gateway. All I can see are the people ahead of me and the arch of the gateway roof.

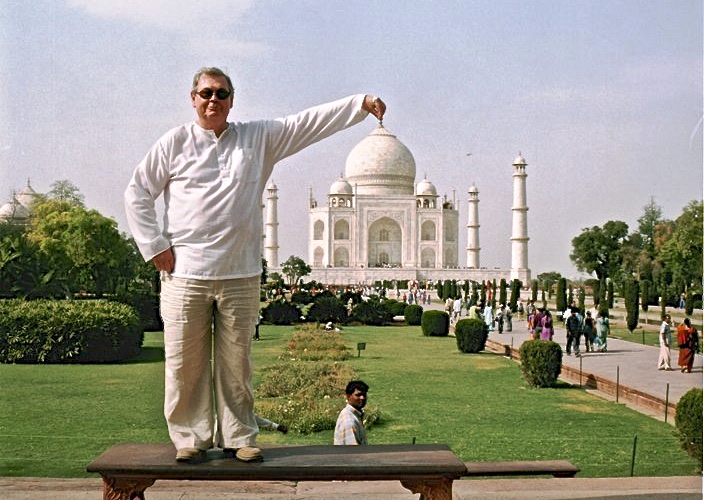

Back in motion, step by step, and… there it is. And yes, it strikes my mouth and my eyes wide open. The whiteness of the Taj seen from the darkness of the gateway is indeed an enchanting sight. As the crowd moves forward and I finally get a better view from the elevated platform, the Taj seems to zoom back and float rather than rise behind the reflecting pool.

The imposing bulbed dome draws the attention first, then the smaller domes. Recessed arched portals soften the straight lines of the four minarets that shoot for the sky. The white marble of the Taj contrasts with the red sandstone of the adjacent mosque and guest pavilion and its elegance with the desolate sight of the drought-stricken Yamuna River. In the background, untilled land stretches to the massive Red Fort, two kilometers away.

In the forefront garden, the reflection of the mausoleum in the water reminisces of a fairy tale castle. One forgets it’s a tomb, a “solitary tear suspended on the cheek of time” for the poet Rabindranath Tagore. For me, it’s a romantic setting enlivened by women in voluptuous, colorful saris. And for the eight million Indians who come every year—plus almost one million foreigners–it’s a once-in-a-lifetime destination.

BETWEEN TALE AND TRUTH

Before entering the Taj Mahal, I slip on shoe covers and step into a jam-packed kind of foyer, where I am immediately shocked. A cacophony fills the echoing space, loud voices resonating against the walls and feet pounding the 22 stairs down to the mortuary chamber. After this unruly approach to a mausoleum, I want to get a closer look at the inlaid stonework but only get a partial view of two cenotaphs. Disappointed and shocked by the commotion, I quickly leave. I notice that ‘photographs are not permitted.’

For a moment, I question the enduring fascination for the interior of the Taj Mahal. Mumtaz and Shah Jahan’s real tombs are in a crypt above the chamber, so people pay their respects or fantasize in front of empty sarcophagi. As for the architecture purists, they cringe at the unplanned addition of Shah Jahal’s own sarcophagus, which ruined the chamber’s original symmetry.

I would later learn that the sound reverberation time is connected to praying for the soul of the departed, hence the intended amplification of the noise. Furthermore, according to Indian intellectuals, romantic love is a foreign concept. In Indian traditional culture, love is connected to deities only, hence the fascination for the Taj’s exceptional love story.

Since romantic love is part of my culture and not an exception, I am more fascinated by the architecture and the visionary ‘labor of love.’ But, in the end, the Taj’s most significant asset is the unique aura of its white marble, and it is not even white.

THE NOT-SO-WHITE MARBLE

Like all Mughal princes, Shah Jahan was expected to excel at trades, crafts, and the arts. His harmonious vision for the Taj was even attributed to his devotion to classical Indian music. He ‘composed’ the Taj, selecting architectural motifs from his family palaces.

He also understood colors and shapes and his expertise in semi-precious stones led to using pietra dura for the floral vines, geometric designs, and calligraphic Koranic messages. But above all, he chose the white Makrama marble–from the Pahar Kua range southwest of Jaipur–to transcend all other Indian architectural masterpieces and all other stones.

A closer look reveals a weathered marble in a hazy white and, much to my surprise, a geometric colored combination of marble, jasper, jade, and mortar that varies from shadow to shimmer and that faded from time and pollution.

No other famous cenotaph in the world nor Indian World Heritage site has engendered as much universal fascination as the Taj Mahal has. Still, I wonder if it is skewed because of the contrasting grim grey of industrious Agra. Let’s imagine the Taj in red sandstone or black marble or a Taj in a crowded urban setting. Hum…

The Taj Mahal stands as a masterpiece of architecture, but it’s perhaps more from the mastery that gave its unique celestial whiteness. Meanwhile, in the neighboring tortuous streets, the descendants of the Taj Mahal’s tradesmen continue to insert painstakingly semi-previous stones in white marble.

Original article 2014 Buckettripper – Revised 2022